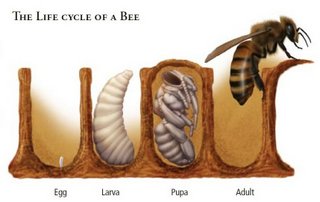

Honeybees belong to the order Hymenoptera, which includes other bees, wasps, and ants. Most Hymenoptera have two pairs of clear wings; all have chewing mouthparts.Some, including the honeybee, can suck up liquids. These insects undergo complete metamorphosis, or change in form, during their development. The four life stages are: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

Bees are perfectly equipped to collect pollen and nectar. They are covered with finely branched hairs that trap pollen as they visit flowers. While visiting flowers, the bees gather pollen from their hairs and store it in pollen baskets on their hind legs. A tongue-like portion of the mouthpart sucks up nectar.

Although man has managed bees for hundreds of years and carried them around the world, honeybees have not been "tamed." Bees in the most modern apiary follow the same instincts as wild bees that live in hollow trees. Successful beekeepers anticipate and work with or around the bees' natural behavior.

Honeybees are social insects, living together in highly organized colonies. Each member has a specific job to do. A single honeybee cannot grow or survive by itself. The three distinct kinds of honeybees in a colony are queen, worker, and drone.

The Colony

In many respects a honeybee colony is like a single animal. Individual bees and castes are like the cells and tissues. When one part is threatened, the whole colony reacts. If an essential segment of a colony becomes diseased or destroyed, the colony often can heal itself. It may divide and become two or more separate colonies.

The colony also changes to survive different seasons. Let's follow the life of a colony through a year.

In mid to late summer, only small amounts of nectar and pollen are brought into the colony. Often no brood are being reared, so the colony does not grow. A fall nectar flow usually allows a small crop of young bees to carry through the winter. The colony needs honey for energy and pollen for protein, minerals, and vitamins to survive the winter and raise brood in early spring. Survival depends on a large cluster of young bees and a good food supply. If the cluster is too small, it cannot generate enough heat to survive the winter. Bees die if their body temperature gets much below 57oF. The colony must be able to make and save heat to survive in winter.

Bees produce heat by digesting honey. They save the heat by bunching together in a tight cluster. The outer layer of bees is an insulating shell that traps the heat in the center of the cluster. The bees on the outer layers periodically change places with inside bees so that none of them become too cold. The cluster tightens or loosens depending on the temperature in the hive.

A large colony with plenty of food can keep the temperature at the center of the cluster around 90oF. This is warm enough to rear brood. They start doing this in late winter. As spring arrives, increasingly more brood are raised. As pollen and nectar are brought in, empty cells in the hive soon fill with brood and food.

Bees do not like to be crowded. If there is not enough room to add comb, some leave in a swarm. Colonies with plenty of space are less likely to swarm and will continue to grow. Beekeepers can keep healthy, productive bees by managing food and space wisely during the year.

Bee Development

All three types of adult honey bees pass through three developmental stages before emerging as adults: egg, larva, and pupa. The three stages are collectively labeled brood. While the developmental stages are similar, they do differ in duration. Unfertilized eggs become drones, while fertilized eggs become either workers or queens Nutrition plays an important part in caste development of female bees; larvae destined to become workers receive less royal jelly and more a mixture of honey and pollen compared to the copious amounts of royal jelly that the queen larva receives.

Bee Brood

- Eggs

Honey bee eggs are normally laid one per cell by the queen. Each egg is attached to the cell bottom and looks like a tiny grain of rice. When first laid, the egg stands straight up on end. However, during the 3-day development period the egg begins to bend over. On the third day, the egg hatches into a tiny grub and the larval stage begins.

- Larvae

Healthy larvae are pearly white in color with a glistening appearance. They are curled in a “C” shape on the bottom of the cell. Worker, queen, and drone cells are capped after larvae are approximately 5 ½, 6, and 6 ½ days old, respectively. During the larval stage, they are fed by adult worker (nurse) bees while still inside their beeswax cells. The period just after the cell is capped is called the prepupal stage. During this stage the larva is still grub-like in appearance but stretches itself out lengthwise in the cell and spins a thin silken cocoon. Larvae remain pearly white, plump, and glistening during the prepupal stage.

- Pupae

Within the individual cells capped with a beeswax cover provided by adult worker bees, the prepupae begin to change from their larval form to adult bees. Healthy pupae remain white and glistening during the initial stages of development, even though their bodies begin to take on adult forms. Compound eyes are the first feature begin to take on color; changing from white to brownish-purple. Soon after this, the rest of the body begins to take on the color of an adult bee. New workers, queens, and drones emerge approximately 12, 7 ½, and 14 ½ days, respectively, after their cells are capped.

Brood Patterns

Healthy brood patterns are easily recognized when looking at capped brood. Frames of healthy capped worker brood normally have a solid pattern with few cells missed by the queen in her egg laying. Cappings are medium brown in color, convex, and without punctures. Because of developmental time, the ratio should be four times as many pupae as eggs and twice as many as larvae; drone brood is usually in patches around the margins of comb.

Races of Bees

Honeybees in North America belong to a single species (Apis mellifera), but several races exist within that species. Races differ in coloration, temperament, industriousness, hardiness, disease resistance, tendency to swarm, and other characteristics.

No single race is best, but Italian bees have a good balance of desirable characteristics. They are hardy, industrious, and fairly gentle. Italian bees have yellow or brown bodies with varying numbers of dark bands toward the ends of their abdomens. They tend to raise young bees early and late in the year, so they need more honey for maintenance than some other races. Italian bees are a good choice for anyone getting started in beekeeping; however, they are susceptible to tracheal and varroa mite infestations.

Modem techniques have produced hybrid bees that have improved the qualities of the best races. Beekeepers can try queens from different queen breeders to learn more about the behavior and honey production of different strains of the same race. Most strains are gentle when handled under the proper conditions. If the bees are not gentle, requeen immediately with a queen from a gentler strain. There is no correlation between honey production and temperament.

Races of bees are often regarded as one would regard breeds of cattle or dogs. However, they should not be. Unlike domestic animals, honeybee races have not been strongly controlled nor bred only by people. They are much more variable than a breed of domestic animal. Honeybees were not significantly genetically selected by humans until recently because basic bee reproduction was not understood until 1845.

Africanized Honeybees

Originally, honeybees were brought to America by European settlers. In 1956, researchers in Brazil were trying to develop a more productive honeybee. They imported queens from Africa because they thought their offspring would be better suited for Brazilian conditions. Unfortunately, some African swarms escaped into the countryside where their queens interbred with the gentler European honeybees. While "Africanized honeybees" have been in Texas for several years, few serious stinging incidents have occurred.

These bees defend their nests more fiercely than European honeybees and swarm more often. Africanized honeybees became known as "killer bees" because of some widely publicized stinging incidents. Venom from an Africanized bee is no more potent than that of a single European honeybee. However, they are quicker to attack anything that enters their territory or approaches the nest, and larger numbers fly to the intruder. Most stinging incidents have involved animals but humans also can be attacked. In some cases the noise or vibration of tractors or mowing equipment has provoked the bees to sting. Chance encounters with individual Africanized bees on blossoms pose no greater threat than encounters with European honeybees. Even though mass attacks arc terrifying and could be life threatening, they are not common. The best defense for avoiding stings from all stinging insects is common sense.

- Source infomation credit to the MAAREC and University of Kentucky